Bone density is a topic that like any discussion regarding the human body is loaded with nuance. As a movement teacher and one-time healthcare professional, I fall into the category of people who believe knowledge is power. Knowledge can also cause fear, though, and that’s not the goal. The goal is to provide you with the most up-to-date information I can locate. The next two newsletters will be broken up into a discussion of the 2017 Lifting Intervention for Training Muscle and Osteoporosis Rehabilitation (LIFTMOR) trial as we discuss maintaining and building bone density in peri/menopause, and then next week we’ll address other options for slowing the rate of resorption. What I hope to convey is that as is always the case with this miraculous human body, there is no one size fits all approach when it comes to taking care of our bones. Why the LIFTMOR trial? It was recognized by the Journal of Bone and Mineral Research as a “high-quality research investigation” that has been validated in follow-up research, and that is rarer than we would imagine when it comes to exercise interventions for bone density in menopausal women.

In conclusion, the LIFTMOR trial is the first to show that a brief, supervised, twice-weekly HiRIT exercise intervention was efficacious and superior to previous programs for enhancing bone at clinically relevant sites, as well as stature and functional performance of relevance to falls in postmenopausal women with low to very low bone mass. Further, that no fractures or other serious injuries were sustained by any participant in our study suggests that HiRIT does not pose a significant risk for postmenopausal women with low bone mass when closely supervised, despite a common misconception to the contrary. In light of the very positive bone, function, safety, and feasibility outcomes of the LIFTMOR trial, we believe HiRIT to be a highly appealing therapeutic option for the management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women with low to very low bone mass. — Watson, et al

What we know about osteogenesis (the formation of bone) is that according to the authors of the LIFTMOR randomized controlled trial, “bone responds preferentially to mechanical loads that induce high-magnitude strains at high rates or frequencies and that weight-bearing loading is vital,” or to put it bluntly, to build density our bones like it hard and fast, and they don’t want to get bored. As previously discussed, though, the natural loss of estrogen that occurs in peri/menopause results in the necessity of stronger perturbations to influence musculoskeletal changes. In fact, for many years, it was widely accepted that maintaining, let alone building, bone density wasn’t even possible for postmenopausal individuals and that the best we could do was slow the rate of resorption, thereby slowing the rate of loss. Recent research demonstrates that this isn’t the case.

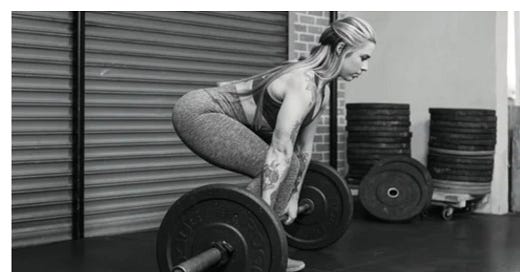

Research indicates that postmenopausal women with low bone mass can indeed build bone density, but currently, the path there appears to be relatively specific. One of the most robustly studied ways to do this is high-intensity resistance and impact training (HiRIT), but that hasn’t historically been prescribed for individuals with osteoporosis due to concerns of increased risk of fracture. The LIFTMOR trial specifically looked at the efficacy of HiRIT in postmenopausal women with low bone mass while monitoring for adverse events. In this trial, researchers took 101 postmenopausal women who were randomized to either eight months of supervised HiRIT (5 sets of 5 repetitions, >85% 1 repetition maximum), or a control group performing a home-based program of low-intensity exercise (10 to 15 repetitions at <60% 1 RM). The HiRIT group performed 30-minute sessions twice weekly consisting of resistance exercises (deadlift, overhead press, back squat), and impact loading via jumping chin-ups to drop landings. At the end of the eight months, participants in the HiRIT group demonstrated increased bone mineral density (BMD) in their spines and the femoral neck/hip, improved femoral neck cortical thickness, increased height, and improvement in all functional performance measures as compared to the control group of home-based exercisers who lost BMD in the spine and hip and demonstrated significantly lesser gains in functional performance. As well, the researchers observed no serious adverse events, the only one being a minor muscle strain where the participant missed two sessions before returning to training.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Change: Fitness in Middle Age and Beyond to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.